Agnosticism

What is agnosticism? There are two different things that are called agnosticism, known as strong and weak agnosticism, or positive and negative agnosticism, or hard and soft agnosticism. (All of these alternate terms, “weak”/”negative”/”soft”, are rather connotationally unfortunate. They don’t really seem like the kind of words people would want to be called. But I figure “soft” is probably the least bad of these options, so that’s the one I’m gonna choose to use.)

Hard agnosticism

Hard agnosticism is the belief that it’s impossible to know whether there is a God or not. So is hard agnosticism about knowledge, as opposed to mere belief? Sort of, but it is ultimately still defined in terms of a belief: Whether you’re a hard agnostic is not determined by whether you have a certain piece of knowledge, but by whether you have a certain belief about knowledge.

No position regarding the existence of God, not even hard agnosticism, can be defined as knowing (or not knowing) that some particular answer to the God question is true. That’s because one of the requirements for a belief to count as knowledge is that the belief is true.

So if, say, theism was defined as knowing that there is a God, you wouldn’t be able to talk about theism without implying that you agree with it. Nor would you be able to talk about atheism without implying that you agree with that. So these things need to be defined as believing (or not believing) something. Theism, atheism, and agnosticism are about what you believe or don’t believe, not about what you know or don’t know. Even hard agnosticism is just a belief about what we don’t know.

People might sometimes describe their beliefs as “knowing”, even if they don’t really mean to assert anything stronger than belief. That’s to be expected, because if you believe something is true, then you probably also believe that your belief has all the other requirements to count as knowledge. So that’s how you might talk about what you think, but that doesn’t mean that these things are actually about knowledge as opposed to belief. Not even agnosticism, and certainly not soft agnosticism.

Soft agnosticism

What is soft agnosticism? When I look at online resources that define agnosticism, they mostly seem to focus primarily on hard agnosticism. But they also (usually rather vaguely) define the soft kind as well. And their descriptions of soft agnosticism do seem compatible with it being about belief, and not actually being about a question of knowledge distinct from the question of belief.

A soft agnostic’s answer to the question of whether there is a God is “I don’t know”. But are people really talking about knowledge as opposed to mere belief when they say that? I don’t think they are.

Answering a question with “I don’t know” would normally most likely mean something like “I don’t know which answer I should give to that question”, or “I don’t know what to believe”. I would not expect someone who gave that answer to mean something like “Whatever I might believe about that, my belief is not properly justified and does not count as knowledge”.

Because as I said before, if you believe something, that generally comes with believing that your belief has all the requirements for it to be knowledge. So it would be pretty strange to believe something, but not to consider it to be something that you know.

Unless you’re saying you have faith, but if you had faith, you wouldn’t be an agnostic, would you? Or is everyone who has faith in God an agnostic, because they merely believe but don’t know that God exists (since their belief lacks the kind of justification that would be required for a belief to be knowledge)? No, they’re not. Or at least they’re not soft agnostics, because that’s not what the soft agnostic’s answer “I don’t know” means.

If you ask people whether there’s a God, you’re looking to find out what they believe. You’re not asking about anything to do with knowledge as opposed to mere belief. And people you ask may answer using an expression that happens to contain the word “know”, but that doesn’t mean they’re randomly deciding to answer that question with something irrelevant about knowledge, instead of actually addressing your intended question of what they believe.

I think people who answer that question with “I don’t know” are not really saying anything about knowledge. All they’re intending to say is simply that they don’t have a belief either way. So a soft agnostic is someone who lacks a belief that there’s a God, and also lacks a belief that there’s no God.

In other words, they have no opinion. They’re undecided. They’re suspending judgment. This is (and should be) the default state for the relation between any person and any claim, until the person comes to have a sufficiently good reason to either accept or reject the claim.

Soft agnosticism is a middle ground between believing that there’s a God and believing that there’s no God. Not to be confused with a middle ground between believing there’s a God and not believing there’s a God. There is no middle ground between those things; you have to do one or the other. But you don’t have to either believe there’s a God or believe there’s no God. It’s possible to have neither of those beliefs, which is what soft agnosticism is.

The principle of agnosticism

So those are the two main meanings that “agnosticism” has today, but the word actually had a different meaning originally. When Thomas Huxley coined the word “Agnosticism”, he didn’t intend it to mean either of the things that people use it to mean now.

What Huxley called agnosticism was the general principle that you should not act like you’re certain about something unless you have good evidence to support your opinion. (This was in response to the principle of faith, which claims that there are things you should believe with complete certainty regardless of the evidence or lack thereof.)

Neither the hard nor the soft modern senses of the word “agnostic” really seem to have much to do with its original meaning. But if I had to pick one, I’d say the soft meaning is closer to the original intent of the word. Because soft agnosticism and the principle of agnosticism are both fairly closely related to the principle of initially suspending judgment by default (which I mentioned a few paragraphs ago). I don’t know where people got the idea that agnosticism meant that knowledge about God’s existence is impossible.

Atheism

What is atheism? There are two different things that some people consider to both be forms of atheism, known as strong and weak atheism, or positive and negative atheism, or hard and soft atheism. (Again, I’m gonna go with hard and soft.) Hard atheism is the belief that there is no God, and soft atheism is a lack of belief that there is a God.

Hard atheism was originally the only thing that the term “atheism” meant. It’s what most people understand that word to mean. It’s how dictionaries say the word is used. And it’s what most philosophers use it to mean.1 But a lot of atheists now consider the broader category that they call “soft atheism” to be a form of atheism too. Some of them even say the soft version is the correct way to define atheism. Where did they get the idea that atheism is a lack of belief? Does it make sense to define atheism this way?

Some people have been trying to redefine atheism as soft atheism since Antony Flew in the 1970s: “Whereas nowadays the usual meaning of ‘atheist’ in English is ‘someone who asserts that there is no such being as God’, I want the word to be understood not positively but negatively.” (At least he acknowledged that his definition was not the standard definition of atheism.)

Some atheist activist groups are pushing this redefinition of atheism, not because it makes more sense, but mainly for practical agenda-driven purposes like inflating their demographic numbers by including soft agnostics as atheists. Are there any good reasons to define atheism as soft atheism? Are there any good reasons not to?

The atheist website EvilBible.com argues against the idea that “soft atheists” should be called atheists at all. That website lists several mostly good reasons to reject the “lack of belief” definition of atheism, and it also gives one particularly bad reason. (Which is the one that it asserts the most vehemently.) The bad reason is that English speakers commonly use “I don’t believe X” to mean “I believe X is false”. That’s not a good reason because:

- The fact that people commonly use language in illogical ways is no reason to accept those illogical uses of language. Normally, when the majority of people think or do a certain thing, intelligent people don’t take that as indisputable proof that the thing must be right. But for some reason, some people seem to think that the popular consensus can never be wrong when it comes to language.

- The fact that some people fail to make a distinction between two different things doesn’t mean there isn’t a distinction there to be made. And it doesn’t mean the distinction should not be made.

- And what are they even trying to prove with this argument? If this common usage argument was valid, what would the conclusion be? That everyone who says they “don’t believe” in God is an atheist? That’s basically the opposite of the point that EvilBible is trying to make! Their argument #6 seems to directly contradict their argument #8, or rather to make the same stupid error that their argument #8 calls out. Why are they arguing against their own position??

“Soft atheism” is not atheism

I think some of EvilBible’s other arguments for limiting the term “atheism” to hard atheism are pretty good, though:

- Some atheists say it doesn’t matter how most people use the word, because only atheists should get to define atheism.

- EvilBible points out that that is not how words get their meanings. The word “baby”, for instance, means what it means because that’s how we all use that word, not because babies decided that that was what it would mean.

- I’d like to also point out (though EvilBible doesn’t mention this) that this principle of exclusive self-definition can’t work, because you would have to already know what an atheist is before you would know who gets to define it.

- When people argue that atheism shouldn’t be defined as only hard atheism because it should be defined by atheists, they are assuming that most atheists want it to be defined as soft atheism.

- EvilBible notes that no evidence is being provided for this idea. (EvilBible then tries to further counter it with some statistics about people who report having “no religion”. But that could mean unaffiliated theists, so those stats are irrelevant and don’t really tell us anything.)

- Anyway, like I said, you can’t solely use what atheists think as the basis for defining atheism, because you would have to already know what an atheist is before you could know who to ask and who to ignore.

- Some atheists think it gives them a debating advantage if they can say they don’t have a belief or are not making a claim, and therefore have no burden of proof.2

- EvilBible responds that the people making the extraordinary claim that there is a God already have a massive burden of proof, so shifting the burden of proof onto them really isn’t necessary.

- Another response I’ve seen (not from EvilBible) is that if atheists want to be rational and to be seen as rational, they shouldn’t be trying to avoid the burden of proof just to try to make things easier on themselves.

- Especially if we’re talking about people who do actually have a belief that there’s no God. Why pretend you don’t? Trying to avoid the burden of proof just gives the impression that you’re unable to justify your position. You do have good reasons to think there’s no God, don’t you? I do. I don’t see why atheists would have a problem with having a burden of proof.

- If you really don’t have a belief that there’s no God, then you may legitimately have the debating advantage of having no burden of proof, because then your position really is the default position, which is soft agnosticism. But then why insist on calling it atheism? And why would you be debating the existence of God, and care about whether you have an “advantage”, if you don’t have an opinion on the matter?

- Etymology doesn’t necessarily tell you how a word should be used today, but for what it’s worth, the origin of the word “atheism” involved combining “atheos” with “-ism” (godless + belief), not combining “a-” with “theism” (without + belief in God).

- The EvilBible article on defining atheism concludes by extensively quoting several reputable dictionaries and encyclopedias. None of them define atheism as a lack of belief. All of them basically define atheism as either the belief that there is no God, or the “disbelief” in or “denial” of the existence of God.

- And they define denial as declaring something not to be true. And they note that denying the existence of God is something agnostics don’t do,3 unlike atheists.

- The dictionaries similarly define disbelief as rejecting something as untrue, or being persuaded that an assertion is not true. One of the dictionaries contrasts unbelief (merely tentatively not accepting that something is true) with disbelief (being convinced that something is false).

- The quoted dictionaries only define disbelief this way half the time, though. And a few of them do include a definition of disbelief as “not believing”. But I’ll note that since people do often (illogically) use that to mean believing that something is false, it’s possible that those dictionary writers didn’t really mean to say that disbelief means “not believing”. Especially since one of the dictionaries that says that is the same one that repeatedly makes the point that to disbelieve something is to believe it’s false.

Here’s another problem (in addition to the ones listed on EvilBible.com) with labeling people who merely lack belief as atheists. I believe this argument was first made by atheist philosopher Graham Oppy:

If not believing that there’s a God is a form of atheism, then by the same logic, not believing that there’s no God must be a form of theism. And if you lack both beliefs (the belief in a God and the belief in no God), then it makes exactly as much sense to say you’re a soft theist as to say you’re an soft atheist.

If it’s wrong to call such a person a theist, then it’s equally wrong to call that person an atheist. Because calling yourself an atheist when you merely lack a belief that there’s a God makes as much sense as calling yourself a theist when you merely lack a belief that there’s no God. If you call “soft atheists” atheists, then you have to accept that a soft agnostic (someone who is neither a hard theist nor a hard atheist) would be both a theist and an atheist.

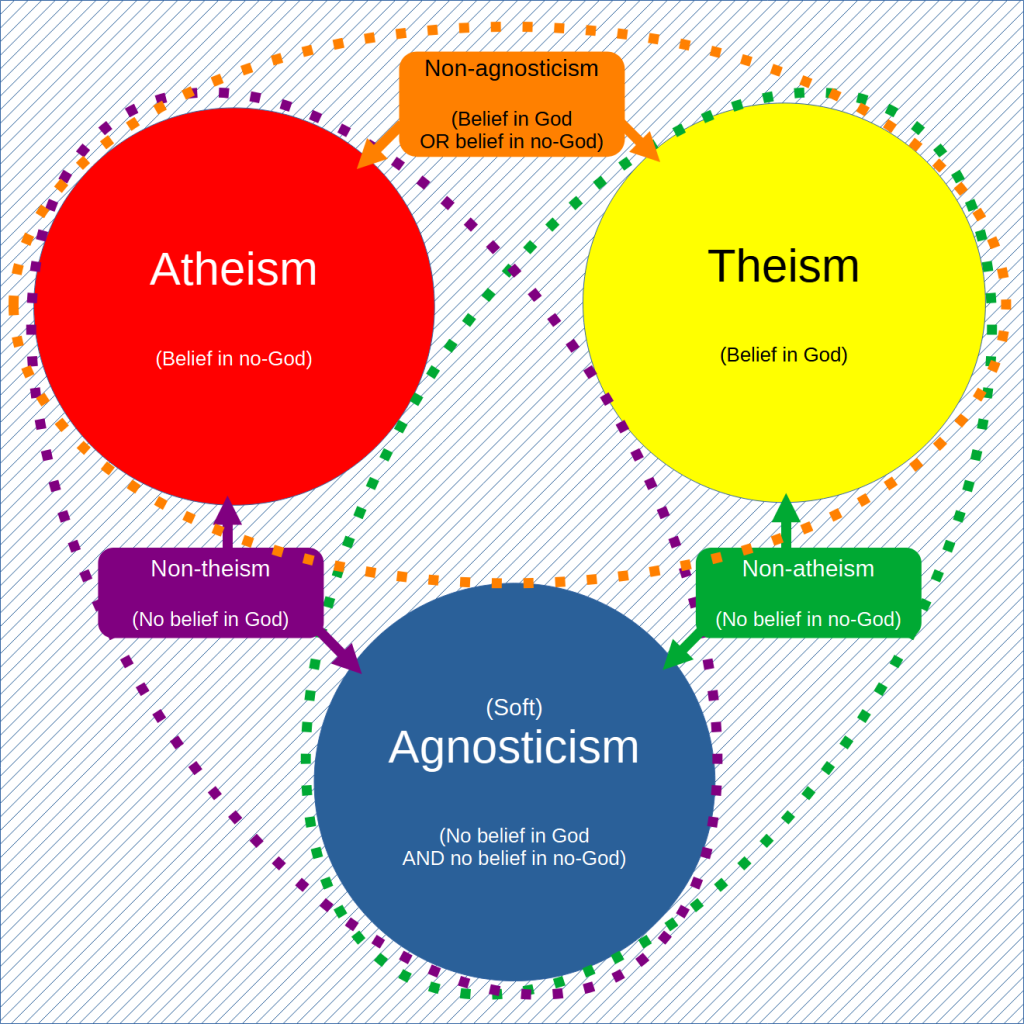

But you can’t be both of those things at the same time, can you? This absurd conclusion, that someone can simultaneously be both a theist and an atheist, shows that there must have been a wrong assumption somewhere, that should be rejected. And that wrong assumption is that mere lack of belief in God is atheism. It’s not. Lack of belief in God is called non-theism. And when combined with a lack of belief that there’s no God, it’s soft agnosticism.

It’s called non-theism

- Everyone is either a theist or a non-theist.

- Everyone is either an atheist or a non-atheist.

- Everyone is either an agnostic or a non-agnostic.

- All non-theists are either atheists or agnostics.

- All non-atheists are either theists or agnostics.

- All non-agnostics are either theists or atheists.

- No one is both a theist and an atheist.

- No one is both a theist and an agnostic.

- No one is both an atheist and an agnostic.

- Anyone who is both a non-theist and a non-atheist is an agnostic.

- Anyone who is both a non-theist and a non-agnostic is an atheist.

- Anyone who is both a non-atheist and a non-agnostic is a theist.

(By “agnostic” here, I mean a soft agnostic. Hard agnosticism is a separate variable, and it’s logically possible to combine that with soft agnosticism, theism, or atheism.)

Agnostic atheism?

Can someone be both an agnostic and an atheist? It depends on what you mean by “agnostic” and “atheist”…

Continue reading Defining agnosticism, atheism, and agnostic atheism