I used to think atheists were smart. Then I visited an atheist social media community.

People were posting all kinds of unbelieverably stupid things in there, like “Why should I have to disprove the existence of your God when you haven’t proven it in the first place?” Do these people really think that the only time something can be proven false is if it has already been proven true? Or do they not know what the word “disprove” means? Or are they just not putting any thought into what they’re saying?

Anyway, here are some things I wish my fellow atheists would stop getting wrong.

Confusing the name of an argument with the name of a response to that argument

I was recently watching a video of an atheist who kept calling the watchmaker argument “the blind watchmaker argument”. But surely the blind watchmaker argument would be a response to the watchmaker argument. Because “the blind watchmaker” is a description of evolution, which can be used as a response to the design argument. And “the watchmaker argument” is basically another name for the design argument, which has nothing to do with a blind watchmaker. So don’t call it “the blind watchmaker argument”. Call it the watchmaker argument.

What is the “God of the gaps” argument? I think atheists are making the same mistake here, using that term to mean a certain kind of argument for the existence of God, when it would make a lot more sense to use it to mean a response to that argument.

When people argue that God is a good explanation for things we can’t explain, those people aren’t thinking of those things as “gaps”. Those of us who disagree with that argument, and who see the gaps as only temporarily unexplained, are the only ones who would use the trivializing term “God of the gaps”. So that should be the name of our argument, not the one we’re responding to.

One more example of this kind of confusion: In a philosophy paper I read, I saw an atheist claim that there was “a defense of The God Delusion that is known as ‘the Courtier’s Reply.’” But “the Courtier’s Reply” is not the name of a defense of the book The God Delusion. It’s a name for a criticism of the book The God Delusion.

Apparently this philosopher has heard a term that atheists use to refer to a certain reply (made by theists) to that book, and has mistaken it for the name of a reply (made by atheists) to that reply. The reply to the reply is actually called “The Meyers Shuffle”. Get your terminology straightened out, people.

“The Israelites made up the story of Lot and his daughters to make their enemies look bad.”

I doubt it. The Bible does claim that the Moabites and Ammonites had an incestuous origin, but it also says the Israelites themselves had incestuous origins. Abraham’s wife was his sister, to name just one example of incest in the history of Israel according to the Bible. Were they trying to make themselves look bad too?

“The Bible says God massacred the babies of Egypt in the last of the ten plagues.”

It says he killed the firstborn of Egypt. I know, that word makes you think of babies, because it has “born” in it. But firstborn doesn’t mean babies! Your firstborn child is your oldest child. You could be any age and be the firstborn in your family, as long as you never had any siblings older than you. Killing all the firstborn would include some babies, but it does not mean that God was specifically targeting babies.

“The Bible has two contradictory versions of the loaves and fishes miracle story.”

The Bible is full of contradictions, but this is not one of them. The two loaves and fishes stories are meant to be about two different events. You can tell because after both of those events happen (in the same gospel), Jesus mentions both of them having happened.

“The Bible is an arbitrary collection of books that were chosen by a vote at the Council of Nicea.“

So says The Da Vinci Code, but that story isn’t known for its historical accuracy. Learn about the real origins of the Bible. The Bible did come to be for a lot of ridiculous bad reasons as a result of mistaken beliefs, obviously flawed methods, and arbitrary decisions, but none of that involved a meeting that decided on the canon all at once.

“The Bible we have now is a translation of a translation of a translation, etc., so we don’t really know what the original said.”

It’s true that we don’t really know exactly what the original scriptures said, because the earliest manuscripts we have are not the earliest versions that ever existed. And it’s true that there have been some versions of the Bible that were made by going through at least two iterations of translation. But biblical manuscripts do still exist in the languages they were originally written in, and Bible translations are generally made by translating directly from those.

“The Bible gets the value of pi wrong.”

Not really. The value implied in the Bible isn’t exactly equal to pi, but neither is 3.141592653589793238462643383279502884197169399375105820974944592307816406286208998628034825342117067.1

How precise do you expect these measurements to be? The Bible doesn’t specify lengths in units shorter than a cubit all that often. If the circumference of a circle is 30 cubits, then the diameter, calculated using the correct value of pi and rounded to the nearest cubit, is 10 cubits. Which is what the Bible says it was. The numbers the Bible gives for this are a perfectly reasonable approximation.

“I don’t believe in things; I accept them, or I understand them.”

Some atheists seem to be averse to the word “believe”. There’s no good reason to be. The concept of “belief” is not limited to supernatural things. And accepting a statement is the same thing as believing it.

A belief is just a person’s mental representation or personal understanding of how things are. No matter what it’s about, and whether it successfully matches reality or not, it’s still a belief. People may be more likely to choose to use the word “believe” when they’re unsure about something,2 but believing something does not mean you’re unsure.3 Everything you know is also something you believe, because knowledge is a type of belief.

There is one good reason you might want to be careful about the “believe in” wording, though: To “believe in” something can mean believing something exists, but it can also sometimes mean having a favorable opinion of it. So if you think someone might plausibly misinterpret you in that way, then you might want to avoid using the words “believe in”.

“It doesn’t matter what you believe; that doesn’t change the facts.”

What you believe does matter, because what you believe influences what you do. If you say it doesn’t matter what you believe, you are saying that it’s okay to have wrong beliefs. That is not a clever way to respond to people who have wrong beliefs.

“Religious beliefs are so obviously absurd, there’s no way anyone actually believes that stuff.”

There are religious people who think the same thing about your views, that there’s no way you can really think there’s no God. You’re both wrong about that. There really are people who don’t think like you.

(Actually, I have seen some interesting arguments for thinking that religious people don’t really believe what they think they believe. But if you’re going to make that claim, you’d better have much better reasons for it than that their beliefs sound absurd to you.)

Plenty of things that sound absurd to some people are honestly believed by a lot of other people. And there are even a lot of things that sound absurd (especially if you don’t know much about them) but are actually true.

“You can’t reason theists out of their belief if they didn’t reason themselves into it in the first place.”

Of course you can. Plenty of people have stopped believing things because of logical arguments, regardless of whether logical arguments were involved in the original formation of their beliefs.4

And if you really don’t think we should be trying to convince people with logical arguments, I’d like to know how you think we should deal with them. Are you saying we should use illogical arguments, and convince people to have beliefs that they won’t have any good reasons for believing? Are you saying we should use psychological manipulation and trick them into changing their views? Are you saying we should give up on reason and use force instead? Are you saying we should just let people keep being wrong?

Stop it. Reason is the best option, and you should not be saying things like this, that discourage people from using it. Stop making excuses for not engaging with people you disagree with. Refusing to debate is not going to help reduce the amount of false beliefs people have. If you find that your arguments are ineffective, maybe you just need to learn how to argue more effectively.

“Most people believe in God for non-rational reasons.”

A poll asking people why they believe in God found that while most people think that other people believe for entirely non-rational reasons, about half or more of respondents said their reason for believing in God was based on some kind of evidence. I’d say their evidence isn’t very good evidence, but they do at least believe for evidence-based reasons, as opposed to something like faith or comfort or upbringing.

And most people do value rationality, even if they may not have successfully applied it to all of their beliefs. I think it’s important not to falsely label people as uninterested in reason. That’s just another lame excuse for not reasoning with them.

“Religion is a mental illness.”

Lots of people have stopped being religious by thinking critically about their religion, learning things they hadn’t been aware of, or considering the evidence and logical arguments. Their religion wasn’t cured by some psychiatric treatment.

Can it really be a mental illness if it’s possible to reason your way out of it, or to have your mind changed just by being exposed to new evidence or information? No, I don’t think that’s consistent with any reasonable definition of mental illness or delusion. To the extent that false religious beliefs are persistent, it’s because of the same cognitive flaws that affect everyone, not because they have some mental illness that you don’t have.

Labeling people as mentally ill just because they’re mistaken about something, or just because you disagree with them, is a dangerous path, and we should be very hesitant to go there. Declaring beliefs to be mental illness would imply that we should be looking for ways to change people’s beliefs with medical treatments instead of by reasoning with them, which should be a horrifying idea to any freethinker.

“The claim that God exists is unfalsifiable.”

Some conceptions of God are unfalsifiable,5 but some aren’t. Sure, maybe there are a lot of theists whose real conception of God seems to be an unfalsifiable one, even if they don’t tend to describe or think of him that way except when their belief in God is being challenged. But since a lot of people have been convinced that the God that they used to believe in doesn’t exist, those people must all have had a conception of God that actually was falsifiable.

And we can assume that plenty of current theists likewise have falsifiable conceptions of God, since those people are no different from the former state of the now-atheists before they changed their minds.

“Hitler was a Christian.”

Maybe, but the evidence is pretty unclear. He did sometimes claim to be a Christian. He also sometimes said he wanted to destroy Christianity. He also denied that he was against Christianity. But maybe that was just because openly opposing Christianity would cost him too many supporters. Or maybe he changed his mind. Or maybe he believed in an unusual version of Christianity that he recognized should probably not really count as Christianity. Whatever he was, he does seem clearly to have been against atheism, though.

“The story of Jesus is copied from earlier stories about gods like Horus, who were said to have been born of a virgin under a star in the east, been subject to assassination attempts as babies, fasted for 40 days, had 12 disciples, performed the same miracles, been crucified and resurrected after three days, etc.”

If you actually read the stories of those gods from sources written before the New Testament, you will not find most of these alleged parallels. The story of Horus’s birth, for example, is that he was born after his mother had sex with her brother who she had reassembled after he was killed and dismembered by another of her brothers. Doesn’t sound anything like the story of Jesus, does it?

(The idea that Jesus was born on the 25th of December probably was copied from the god Mithra, but that claim about Jesus isn’t even in the Bible, so who cares about that?)

“Jesus never existed.”

The idea that Jesus never existed at all (as opposed to the idea that he really lived, but then people made up a bunch of crazy stories about him later, or even in contrast to the idea that we just don’t know if there was a real Jesus or not) is a fringe theory that most scholars do not accept.

Before you make such a strong claim, think about whether you have good reasons for it. Do you really have compelling enough evidence to think it’s true? And even if you could prove that the gospels were made-up stories about a made-up person, rather than made-up stories about a real person, what good would that do?

If the whole Jesus story was completely made up, and not at all based on the life of a real person, then why did the writers give him a name and hometown6 and other details that didn’t match the prophecies they were trying to make him fulfill? And why would they include things in the stories that make him seem suspiciously like a fake, like the part where he can’t fool the people who know him best? The most likely explanation for these things being included in the stories would seem to be that there was a Jesus, and these facts about him were too well known to deny.

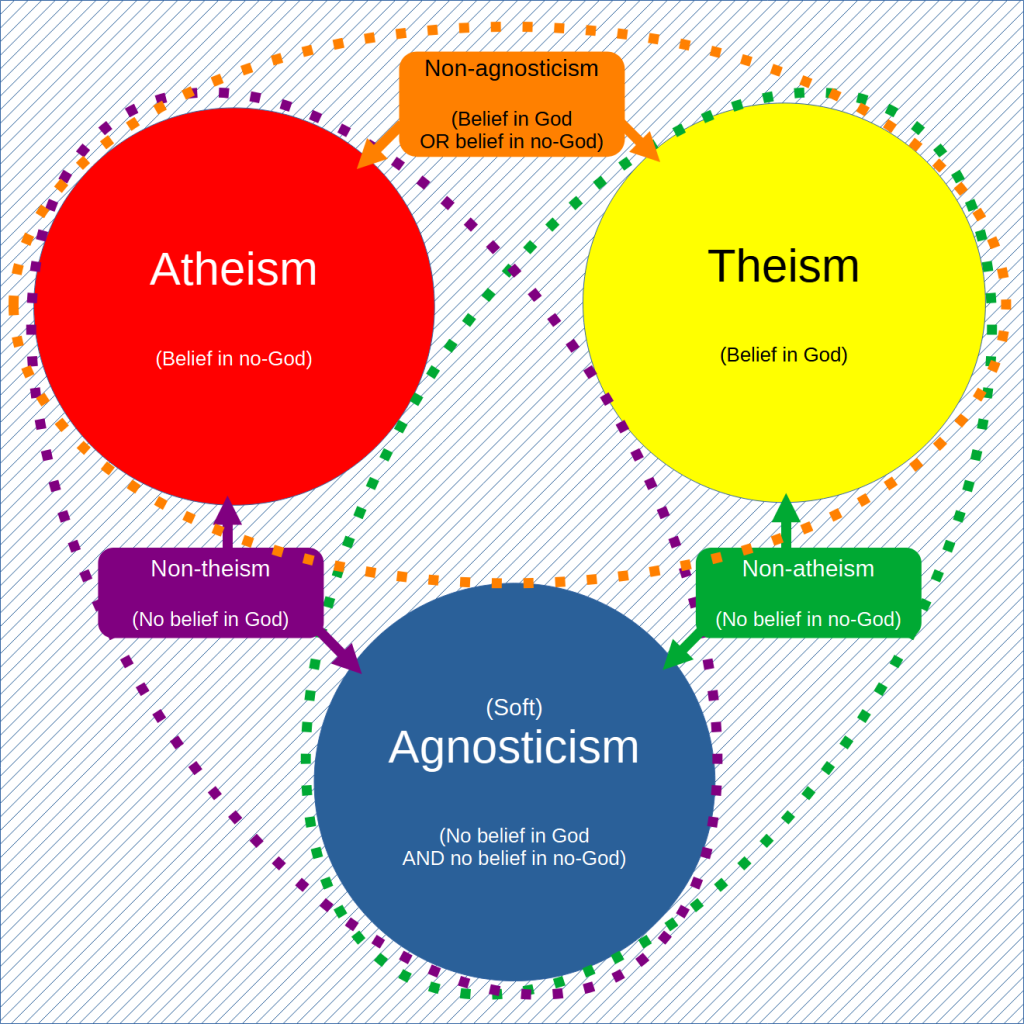

“We are all atheists regarding most gods. Some of us just go one god further.”

We are all nonbelievers in most gods. We are not all atheists. People who believe in one God are monotheists, not atheists.

“When you understand why you dismiss all the other possible gods, you will understand why I dismiss yours.”

Not necessarily. Not everyone rejects other religions for the same reasons. Sometimes the reason religious people reject other gods is that their religion tells them there’s only one God. Knowing that is not going to help them understand why you reject theirs.

“Historical dates should be written with the religiously neutral terms BCE and CE, not BC and AD.”

Jesus is the only reason we count years starting from around 2000 years ago. No matter which terms we use for it, we are still using a Christian calendar. So why pretend we’re not? If you’re not going to actually invent a new and improved calendar system with an objectively better starting point and convince everyone to use it, just admit that we are all using a Christian calendar. Dishonestly calling something by a different name doesn’t change what it is.

If we’re not going to insist on renaming the days of the week just because we don’t believe in the gods they’re named after, and renaming the months of the year just because we don’t believe in the gods they’re named after, then we don’t need to change the terms BC and AD just because we don’t believe in the god those are named after. Just use BC and AD. They’re easier to tell apart than BCE and CE.

“Morality can be explained by evolution.”

Not exactly. Evolution may be a good explanation of how we came to have some of the inclinations we have that happen to align with morality, but evolution can’t be what defines morality, for reasons similar to some of the same reasons that God can’t be what defines morality.

Did we evolve to be inclined toward certain behaviors because those behaviors are good? Then goodness is something that exists apart from evolution, and is not fully explained by it. And anyway, that’s not how evolution works. Evolution doesn’t have goals like that.

Or are good behaviors good just because that’s what we evolved to do? No, that would mean that any behavior resulting from evolution would have to be good. But that’s not true. Evolution also produces behaviors that are not morally good. Sometimes it produces behaviors so wildly opposed to morality that it would never occur to humans to do such things. Unless you want to argue that every behavior that occurs in nature is actually good, because it comes from evolution, you shouldn’t be claiming that evolution is where morality comes from.

“Galileo was punished by the anti-science Church for disagreeing with their dogma that the Earth was the center of the universe.”

The Church was wrong to censor and punish Galileo for what he said, but this was not a science vs religion thing. The Church was open to new scientific discoveries, and had been for centuries, as long as there was actually strong evidence for them. But as of Galileo’s time, there was nothing particularly scientific about rejecting geocentrism.

The Church was very supportive of Galileo, until he started saying the scriptures should be reinterpreted to conform to his unproven pet hypothesis. They didn’t object to heliocentrism because it was heretical; they objected to it because there wasn’t enough evidence for it yet.7

Heliocentric models predicted that there should be parallax and Coriolis effects that nobody actually observed until decades after Galileo died. Based on the evidence available in Galileo’s time, the heliocentric model wasn’t any more reasonable a conclusion than the geocentric model. The ancient Greeks had not discovered heliocentrism long before; some of them had decided to believe in heliocentrism for wildly unscientific reasons, and happened to be right.

More recently, Copernicus had also proposed a sort of heliocentric model, but his reasons for preferring heliocentrism weren’t particularly rational either. His model didn’t explain the evidence available at the time any better than geocentrism did. And because Copernicus didn’t realize that orbits were elliptical, his model was overly complex, so Occam’s razor says the Copernican model was not to be preferred. And that flawed model is the one Galileo promoted, using arguments already known to be wrong, like saying the tides prove the Earth is moving.

Then Kepler had come up with a model (involving elliptical orbits) that would turn out to be more accurate than Copernicus’s, but there still wasn’t enough evidence available at the time to tell which model was more accurate. Anyway, Galileo completely ignored Kepler’s insight, and dogmatically refused to even consider the possibility that orbits weren’t perfect circles. Galileo’s attitude in this matter was decidedly less scientific than that of the Church.

“When an apologist says you need to be more knowledgeable about theology before you can reasonably argue that God doesn’t exist, that’s like if the emperor’s courtier replied to the assertion that the emperor’s new clothes don’t exist by saying by saying that the child didn’t have enough expertise on invisible fabrics to be qualified to make that judgment. If the thing in question doesn’t even exist, then there’s nothing to study, and any attempt at a sophisticated analysis of the topic would inevitably be meaningless and pointless.”

You may not need to be an expert on something before you can prove that it doesn’t exist, but you do need to at least know enough to literally know what you’re talking about. Otherwise, for all you know, you’re more like a kid who says the emperor has no clothes… because the kid mistakenly thinks the word “clothes” means “antlers”.

If the version of God you’re disproving is not what believers actually mean by “God”, or if the version of an argument you’re refuting is not an accurate representation of the argument that believers actually make, then you do indeed need to learn more about what they believe before you can say anything that will actually be relevant to their beliefs. You do need to know enough to know what people actually believe, or else you’ll just be attacking a straw man. You can’t meaningfully argue against a claim unless you have an accurate idea of what the claim is.

Imagine a creationist dismissing a defense of evolution as a “courtier’s reply”:

“When I say evolution doesn’t exist, the evolutionist will say I don’t even know what evolution is, and that I don’t have enough expertise on biology to be qualified to judge whether evolution makes sense.

“This is like if a courtier replied to the assertion that the emperor’s new clothes don’t exist by saying the skeptic doesn’t have enough expertise on invisible fabrics to be qualified to make that judgment.

“If the thing in question doesn’t even exist, then there’s nothing to study, and any attempt at a sophisticated analysis of the topic would inevitably be meaningless and pointless.”

Do you still think that’s a good argument? It’s not, no matter who’s making it. You can’t dismiss an objection to your argument on the grounds that it doesn’t matter because the thing you’re arguing about doesn’t exist anyway. The nonexistence of God is a possible conclusion we’re trying to evaluate, not a premise that we can start with. You have to resolve all the potential flaws in your disproof of God first. Until you’ve done that, you haven’t actually established that God doesn’t exist, which means you can’t use that as a premise for any further reasoning.

When people say you’re wrong because you’re not an expert, are you sure they’re even saying that’s how you’re wrong? Maybe what they’re saying is not that “because you’re not an expert, it inherently logically follows that you’re automatically wrong”. Maybe they’re saying you’re wrong, and then they’re additionally suggesting that the fact that you’re not an expert could explain what caused you to be wrong. Showing how you’re wrong is something else, that they can do separately. If all you’re refuting is the assertion that you’re not an expert, you’re not actually addressing what they think you’re getting wrong.

By the way, the courtier analogy doesn’t actually fit the situation that it was originally used to describe. The term “courtier’s reply” was first used to refer to theists who said Richard Dawkins should have done more research on theistic beliefs and arguments before writing a book attempting to refute them. Those theists weren’t saying Dawkins needed to be an expert before he personally could disbelieve in God. They were saying he really should have done more research before writing a book trying to convince people that God doesn’t exist.

“If you can’t explain where God came from, God is useless as an explanation for anything else.”

Continue reading Things atheists get wrong