An eagle planted a vine. The vine grew toward the eagle, until another eagle came and watered the vine, and then the vine grew toward that eagle. Then some people came and pulled the vine out of the ground, and it withered and died.

Continue reading The Parable of the Gardening EaglesTag Archives: god

The Parable of the Failed Vineyard

Someone tried to plant a vineyard, but the grapes he grew weren’t any good. He couldn’t figure out what he had done wrong, so he decided it must be the grapes’ fault. And so he destroyed his vineyard.

The end.

The moral of the story

Don’t over-water your vineyard.

Continue reading The Parable of the Failed VineyardHas anyone ever given anything to God?

Paul asks: Who has ever given to God, that God should repay them? He seems to think the obvious answer is that no one has ever given God anything. Like it’s impossible to do that, or something. But that’s obviously not true.

Continue reading Has anyone ever given anything to God?The Parable of the Rich Thief

Once there was a rich man and a poor man. The poor man had nothing but one lamb, but he loved it much more than the rich man loved any of the many sheep he had. When a traveler came and stayed with the rich man, the rich man needed a sheep to make a meal for the traveler. But instead of using one of his own sheep, the rich man stole the poor man’s lamb. King David said the rich man should be killed, and be forced to give the poor man four new lambs.

Continue reading The Parable of the Rich ThiefShould people blaspheme God?

No.

God commanded his people through Moses not to blaspheme him. He said blasphemers must be cut off from Israel.

When one half-Israelite man blasphemed God’s name, the others weren’t sure what God wanted them to do. So God clarified that anyone who blasphemed his name was to be stoned to death. Even if they were foreigners. So they did.

When Eli’s sons blasphemed God, God rejected them and put a curse on their family forever, with no hope of atonement. Even though God had promised that they would be his priests forever.

The king of Assyria and his commander blasphemed God, so God got the king’s sons to kill him with swords. And when the king of Tyre called himself a god, God said he would send the king’s ruthless enemies to prove his mortality to him.

God had an angel kill Herod Agrippa just because other people called him a god. God didn’t even give him a chance to say what he thought about it.

According to Mark, Jesus said blasphemy against the Holy Spirit is the only sin that God never forgives.

Maybe?

According to Matthew and Luke, though, Jesus also said that “every kind of sin and slander can be forgiven“. And that “anyone who speaks a word against the Son of Man will be forgiven“. So if you sin by slandering the Holy Spirit, God might forgive you. And if you sin by slandering Jesus, God will definitely forgive you.

Yes.

Continue reading Should people blaspheme God?God must be crazy

Random, impulsive, and pointless acts of God

God teams up with Satan to torment Job, the most righteous and godly person in the world, including by killing all his children. God does this just to see if Satan is right that Job’s love of God is conditional on God being good to him. Satan does turn out to be right about that, but God never admits it.

God tells Abraham to murder his son, then stops him at the last second and says it was just a test. A sane God would have said Abraham had failed the test, but this God is actually very pleased that this guy was willing to spontaneously murder his child just because a voice in his head told him to.

God decides he hates Esau, when Esau has done nothing wrong, because he hasn’t even been born yet.

God warns Laban in a dream that he supposedly needs to “be careful not to say anything to Jacob, either good or bad”. Laban then completely ignores this pointless command, with no consequences.

God talks about God in the third person, then apparently realizes that’s kind of confusing, and feels the need to clarify that he wasn’t talking about some other God.

God manipulates people into selling Joseph into slavery, falsely accusing him and sending him to prison, then putting this prisoner-slave in charge of a whole country just because he claims to know the “meaning” of some surreal dreams, and letting him unjustly oppress the country he now rules… all because God can’t think of a better way to “save” people from the famine that God is causing.

God chooses Moses to be the one to speak to Pharaoh about letting his people go. But then God decides to let Moses’s brother Aaron do the actual speaking, while Moses tells Aaron what to say, and God tells Moses what to tell Aaron to say. Why does Moses need to be involved at all, then? Just because God can’t admit that he was wrong to choose Moses? He’s making Moses into a pointless middleman. (But Moses still gets all the credit as the leader, for some reason.)

When some of the people of Israel ignore God’s instructions, God gets mad at Moses and acts like he’s the one disobeying.

God apparently decided to help his chosen people in battle only when Moses had his hands up in the air.

God communicates with the Israelites through Moses incredibly inefficiently. He needlessly makes Moses go up and down a mountain so many times, the author of Exodus repeatedly fails to keep track of where Moses last was. God’s reasons for Moses to go up or down the mountain are things like:

Moses needs to be on top of the mountain to talk to God (even though he’s already been talking to him just fine from the bottom of the mountain). And Moses needs to deliver messages between God and his people (even though God already knows what the people said). And Moses needs to go warn the people not to get too close to the mountain (even though he’s already done that).

God’s Ten Commandments include a rule against making images of anything. Apparently God hates art.

God’s law says it’s okay to kill a thief who breaks into your house, but only if you do it at night.

God thinks there is somehow “guilt involved” in giving him gifts, which could potentially make those gifts unacceptable. But as long as Aaron is wearing a “holy to the Lord” label on his forehead, it’s okay. Apparently God can’t remember which people are holy unless they’re labeled. God also requires Aaron and his descendants to wear special underwear when they go near his stuff, and threatens to kill them if they don’t wear the right underwear.

God demands that people put sheep blood on each other’s ears, thumbs, and toes. Why? Because that’s part of the requirements to become a priest, because God said so. But the priests had better not go near God’s tent or altar with unwashed hands or feet, or he might kill them.

God tells the Israelites to go on to the promised land without him, because he is so lacking in self-control that he expects he wouldn’t be able to stop himself from murdering them all if he had to spend any time around them. (Then he forgets about that problem and decides to go with them anyway.)

After Moses breaks the tablets of the law, God says he’s going to write the same laws on some new tablets. But then he makes Moses write the laws on the new tablets, and they turn out to be almost completely different from the laws that were on the original tablets.

God gets mad at his people for doing what one of his prophets wanted them to do, and so God starts killing tens of thousands of his people. But then he sees Aaron’s grandson stick a spear through a couple of people who are having sex in a tent. This makes God very happy, and he decides he doesn’t need to kill any more Israelites for now.

For some reason, God thinks he needs to forbid his people to go back to the place he rescued them from. That seems completely pointless, unless they weren’t actually as bad off there as God’s book makes it sound…

God’s law says if you find a person who has been killed, and you don’t know who did it, you can just blame it on a cow. Break the cow’s neck, and God’s bizarre sense of justice will be satisfied. Who cares if the actual killer is still on the loose?

Apparently God would have punished someone if that offering hadn’t been made, but now God thinks no one needs to be punished. That means either that murderers can bribe God to ignore what they’ve done, or that whoever God was going to punish wasn’t guilty, but God doesn’t care about that and would have killed them anyway, but now he’s decided not to kill them, because they killed a cow.

Moses repeatedly has to stop God from killing off his entire chosen nation when he gets mad at them for doing perfectly reasonable things. And when God changes his mind about that, it’s always for selfish reasons, like when Moses convinces God that killing off his people would be bad for God’s reputation.

When Joshua wants to know why God has stopped helping his people, God explains that one of them has stolen something that God claims belongs to him. And therefore God is angry with the whole nation for what one person did. God tells Joshua to have each tribe come before him so God can say whether the culprit is in that tribe or not, and then do the same with each clan in the guilty tribe, and so on, until they narrow it down to the individual thief. But God is already speaking directly to Joshua, so why doesn’t he just tell him who’s guilty right now?

God wants to talk to young Samuel, but when he calls to Samuel, he doesn’t say who’s calling. After God sees that this isn’t working because Samuel thinks it’s somebody else calling, God just does the exact same thing a few more times, until somebody happens to somehow figure out what’s going on.

Saul makes an offering to God to make sure he has God’s favor. Then Samuel comes and tells him that God has rejected him as king, for supposedly breaking some command. I have no idea what command Saul is supposed to have broken by making an offering to God.

When Saul idiotically decides to put a curse on any of his men who eat anything that day before they defeat the Philistines, God seems to take that seriously. After Saul’s son, who isn’t even aware of the curse, does eat something, God refuses to communicate with Saul, except to let him know that his son has angered God.

God communicates this after Saul says that whoever is responsible will have to die, so apparently God wants Saul to kill his son, and now Saul wants to, too. But then Saul’s men prevent his son from being killed, and neither Saul nor God seem to object.

When Saul and his men are trying to hunt down the man who God has chosen to be the next king, God makes them strip their clothes off in public and lie there naked all day and night.

2 Samuel 24 begins by saying that God’s anger burned against Israel. It doesn’t say they had done anything to provoke such a reaction. God seems to just get angry first, and then afterward, he gets somebody to do something that he can claim is wrong, so he’ll have an excuse to kill tens of thousands of those people he had been feeling angry at. Who aren’t even the ones who end up committing the alleged wrongdoing.

David says he has heard two things, even though God only spoke one thing. He says what the two things were, and neither of them make any sense for God to say. Apparently God talks to himself and reassures himself about how powerful and just and loving he is.

David also says God announced that he has a dove with gold and silver on its feathers while people sleep among sheep pens.

Solomon claims that the results of casting lots are actually controlled by God. If he’s right, that would mean that God’s decisions are so completely random that they’re indistinguishable from the results of a random decision generator.

God sends down fire to kill a hundred men because their leaders tried to tell a prophet what to do. He sends bears to kill a bunch of little boys for making fun of a bald prophet. And he gets someone trampled to death for doubting the bald prophet’s prediction.

God has a day of crying out to the mountains.

God makes people… queef? Painfully?

In the middle of talking about his plans for mass destruction, God randomly says he’s crying out and gasping and panting like a woman in childbirth.

God says someone is going to wear her children as ornaments, because he thinks that’s what brides do.

The first vision God shows his prophet Jeremiah is an almond tree branch, which has no purpose other than to make an opportunity for God to make a pun.

God makes Jeremiah buy a belt, bury it, and dig it back up only when it has become ruined and useless. The only purpose of this is so Jeremiah will have a comparison to make when he talks about God’s plans to make his people “ruined and useless”. But that won’t be very meaningful to the people he’s talking to, since they didn’t experience the thing with the belt.

God makes Ezekiel do all kinds of outrageous and silly and unpleasant things that are completely unnecessary. He starts by confusing Ezekiel with a vision of bizarre otherworldly creatures when he’s not even a prophet yet, which God never explains and which seems to have no purpose. Then he tells him he has to go prophesy to Israel, though God doubts they’re going to listen to him. And then the first thing God requires Ezekiel to actually do is eat a scroll.

Next, God makes Ezekiel besiege a drawing of Jerusalem. Then he ties Ezekiel up, and makes him lie on his left side for 390 days, and on his right side for 40 days. And even though he’s tied up, God expects Ezekiel to somehow still be besieging his drawing. He also expects him to bake bread over burning poop and eat it, while he’s tied up.1 And he instructs Ezekiel to be afraid while he eats and drinks. That’s not how emotion works, God. You can’t just tell people how to feel.

God makes Ezekiel shave with a sword, then burn some of the hair, and attack some of it with the sword. And he says he’s going to punish his people by shaving them. Then he tells Ezekiel to talk to the mountains, more than once. (He makes Micah talk to mountains too.)

God tells Hosea to name his daughter “Not Loved”. This God sucks at picking names.

God wishes for God to rebuke Satan. Why doesn’t he just rebuke Satan, instead of talking about himself in the third person like that?

God says he’s setting a stone with seven eyes in front of a priest who is apparently the branch that he’s talking to the priest about as if the branch isn’t there yet and which will supposedly also be a king.

God threatens to curse the priests’ blessings. And then he says he’s already done it, without giving them any time to do anything about it, so what was the point of the threat?

The Bible says Jesus is God, so of course Jesus is crazy too. His own family thinks so.

John the Baptist baptized people by immersing them in water, but he said he was just preparing the way for Jesus, who would baptize people with fire.

John thinks Jesus should be baptizing him, not the other way around. Which makes sense if Jesus is indeed God, since he wouldn’t need anything done to him that baptism supposed to do for people. Baptizing God would be pointless. But Jesus insists on getting baptized anyway. I don’t know what that’s supposed to accomplish, unless it’s to show that Jesus is not God.

Jesus asks what reward you’ll get if you only love those who love you. You’ll get love, duh. But what kind of person thinks you need a reward for loving?

Jesus says the crowds don’t need to go away, even though it’s getting late. Then after he feeds the crowds (who were going to go eat anyway), he immediately sends them away. Sounds more like they didn’t need to stay.

When a man begs Jesus to drive the demon out of his son, Jesus’s response is to randomly start insulting his generation.

Jesus says that when he returns, some people will be “taken” and others left. But when his disciples ask where those people will be taken, Jesus tells them where vultures gather, instead of answering the question. As a result of Jesus failing to answer that question, a lot of people now mistakenly think he was saying that some people will be “raptured” to heaven.

Jesus asks a woman for a drink, when what he really wants is for her to ask him for a drink.

When Jesus is expecting to be betrayed soon, he tells his disciples they need to sell their cloaks so they can buy swords. But then when one of them tries to use his sword to defend Jesus, Jesus seems to disapprove of them using swords at all. So why did he tell them to buy swords?

When the elders ask Jesus if he’s the Messiah, Jesus responds that if he asked them, they wouldn’t answer. Because they don’t know the answer, because he hasn’t told them. But he seems to think the fact that they wouldn’t have answered means he doesn’t have to answer. Even though the reason for them not answering obviously doesn’t apply to him.

The reason God loves Jesus is that he got himself killed and then came back to life. That’s a pretty weird reason to love someone. If Jesus hadn’t died, or if he had died by accident, or if he had stayed dead, God wouldn’t love him.

Jesus wants to indicate how Peter is going to die, so he says a bunch of confusing stuff about getting dressed and going places and feeding sheep, which doesn’t make it at all clear how Peter is going to die.

God talks to himself, which some people would say only crazy people do. I don’t think that’s right, but would a sane person talk to himself indirectly by telling other people to talk to him, and then telling them what to say to him because they don’t know what to say to him, but then the things he tells them to say to him are just wordless groans?

God makes Christians seem crazy too, by getting them to say things that make no sense to anyone else. He goes further and gives them the completely pointless “gift” of talking completely unintelligibly so that no one has any idea what they’re trying to say, including themselves, which makes everyone think they’re crazy.

God sends Paul and his colleagues with God to talk to God.

God is going to present undead people to himself.

The book of Hebrews claims that God said a bunch of stuff about himself in the third person, for some reason.

Revelation predicts that Jesus is going to come with a double-edged sword sticking out of his mouth, so he can fight people using the sword of his mouth.

Jesus is going to angrily trample the world’s grapes (either that or he’s murdering trillions of people) in a big winepress, causing a massive flood of blood.

God is going to invite all the birds to eat all the people.

Forgetful, confused, and delusional

God threatens Egypt with plagues that will kill some of their livestock… after he’s already sent a plague that killed all the livestock of Egypt.

For the Passover ritual, God says you have to use a lamb, but you can take it from either your sheep or your goats.

When Moses asks to see God, God tells him he can’t see his face, because no one can see God and live. This is when Moses is already in the habit of speaking with God face to face, so what God is saying is a completely obvious lie. The Bible says people can see God’s face, and that seeing it is desirable, not deadly. Not seeing God’s face is what’s deadly.

God likes to describe himself as compassionate, forgiving, and slow to anger, even though he is constantly getting angry and killing people over nothing. And when God decides to punish people, a lot of the time he ends up punishing the wrong people for some reason.

God’s law says if a man has lost his hair and is bald, and he has a certain kind of sore on his bald head, then the bald man has to let his hair be unkempt.

God says the inhabitants of the promised land have already been expelled from the land, when that obviously hasn’t happened yet. God insists that he has punished the land of Canaan. He didn’t just punish the people there, who were having sex with animals and stuff. He specifically says he also punished the land, for the land’s sin.

God demands that his people love him with all their heart and soul and strength. That is not how love works. You can’t just tell people to love you.

God says when you attack a city, you shouldn’t cut down its fruit trees, because they’re not people. Because there’s no point in doing something if it doesn’t involve killing people. Then he says you can cut down the non-fruit trees. Because those trees are people, I guess.

God is apparently so worthless that he has worthless inanimate objects for rivals, and he’s very insecure about it.

Saul supposedly disobeys God, and God rejects him as king of Israel. (What Saul has actually done is make an offering to God, which God thinks is somehow a reason to abandon, torment, and kill Saul.) Then Saul supposedly disobeys God again, and God rejects him as king of Israel again, apparently having forgotten that he’s already done that.

God claims that when he chooses people to become kings, he judges them by their character, not their appearance. God then promptly chooses as the new king of Israel a handsome man, who will go on to do way more evil than the king he’s replacing.

This is typical for God. Whenever he personally chooses a new king, it’s generally someone with a striking appearance, who turns out to be evil. Which is exactly the opposite of what you’d expect based on how God says he chooses kings. Either God is extremely incompetent at this, or he wants his kings to be evil.

According to Solomon, God told David that since the day his people left Egypt, he had never chosen anyone to be ruler over Israel. That’s obviously not true, since the person God was talking to was someone God had chosen to be ruler over Israel. And he wasn’t even the first one. Why does God keep making all these bizarrely obviously blatantly false claims?

God tells Elijah to go out and stand on a mountain. When Elijah does, God asks him what he’s doing there, apparently having already forgotten what he had just told Elijah to do.

God tells Isaiah that all these people are annoying him by bringing him meaningless offerings of dead animals. God asks who has asked this of them, apparently having forgotten that he has. Later, God complains that his people aren’t giving him any sacrifices, and then right after that, he claims that he never told them to make sacrifices for him. So what’s he complaining about?

God wishes there were briers and thorns confronting him, so he could march against them in battle and set them all on fire. Or maybe let them make peace and come to him for refuge. Whichever.

God thinks of himself as a righteous savior, but his idea of righteousness and salvation doesn’t rule out letting everyone on earth die.

After describing his plans to poison his people, pursue them with a sword, kill their children, and ruin their cities, God describes himself as “the Lord, who exercises kindness“.

God says he intends to fulfill a promise that he has already fulfilled.

God implies that the children of the people he’s talking to are dead. Then he says their children will come back, acting like the only problem is that they’re in another country right now.

God says some particular houses will be filled with dead bodies, forgetting that he just said those houses have been torn down so the materials can be used for other things. Those houses can’t be filled with anything.

God tells people he will restore them to their land, when those people have never had to leave their land in the first place.

God calls Sodom Jerusalem’s “younger sister“, even though the Bible indicates that Sodom was destroyed about 700 years before the Israelites settled in Jerusalem, so Sodom is actually much older.

When God decides to turn against his chosen people and attack them and rip them open and devour them like a wild animal, he calls himself their “helper”.

God describes a city that’s being flooded as being “like a pool whose water is draining away“. Like draining is the problem.

God tells Zechariah to say that God says something that makes no sense for God to say. Something about having been sent by God. God wants us to know that God was sent by God?? Why does God keep saying he sent himself to deliver a message from himself?

God tells his people to plead with God to be gracious to “us”. So God is among the people God wants to punish? And he needs other people to intervene and try to convince him not to punish himself??

Jesus says anyone who does God’s will is his brother and his sister and his mother. And the Bible says Jesus did God’s will, therefore Jesus is Jesus’s brother and Jesus’s sister and Jesus’s mother. In addition to being his own father.

Because people think the kingdom of God is going to appear at once, Jesus tells a parable… which doesn’t address that issue at all.

Jesus thinks if people didn’t call him a king, stones would.

Jesus tends to ignore the questions he’s been asked, and respond by saying something barely relevant or completely unrelated instead. Jesus starts to answer a question about when everything will end. But he ends up just stating whether certain things will end. When people ask Jesus where his father is, instead of answering, he just tells them that they don’t know his father.

When Peter asks him who he’s talking to, it says “Jesus answered” …but he doesn’t actually answer the question. Jesus instead asks something about the story he was telling. That’s not an answer. And when Peter asks him where he’s going, he doesn’t answer that either. He just says his disciples can’t follow him there.

Jesus explains why he thinks he doesn’t need to wash his hands before he eats. Then he tells a couple of brief parables, or mixed metaphors, or something. These metaphors are to explain why it doesn’t matter that he offended the Pharisees with his opinions. But then when Peter asks him to “explain the parable”, Jesus instead goes back to trying to justify his opinions on hand washing. His response to Peter says nothing about the topics of those parables, or about parables at all. But he still acts like he thinks he’s “explaining the parable”.

Jesus says people shouldn’t be surprised by him claiming that they need to be born again. But instead of explaining himself when asked, he says something dumb about the wind.

Jesus gives his followers a new command: to love each other. That’s still not how love works. But Jesus thinks everyone will be able to tell who is a disciple of Jesus, by the fact that they love each other. Apparently he thinks his people are the only ones who do that.

Jesus wants his disciples to break and eat his body and drink his blood. He wants everyone to eat his flesh and drink his blood, because he thinks he’s bread. And don’t forget to drink his spirit, too.

Jesus complains that none of his disciples have asked him where he’s going… after Peter and Thomas have both asked him just that, and he has refused to actually answer their question.

Jesus says everyone who believes in him will be able to do all the miraculous things he did, and more. He says everything is possible for believers, because they can ask him for anything they want, and he will do it. All it takes is the tiniest amount of faith, and you can move mountains, according to Jesus. Yet in reality, there are lots of people who have way too much faith, and not even they can move mountains.

You don’t even have to actually test this claim to see that Jesus is wrong. Just think about what will happen if two believers2 ask Jesus to do two incompatible things for them. They’re not both going to get what they asked for. Jesus’s absurd claims that Christians can do anything are clearly false, which should have been obvious to everyone, including him, and he should have thought of that before he made those claims.

God considers slaves to be free when they become Christians, and considers free people to be Jesus’s slaves when they become Christians.

Stupidity

Continue reading God must be crazyDefining agnosticism, atheism, and agnostic atheism

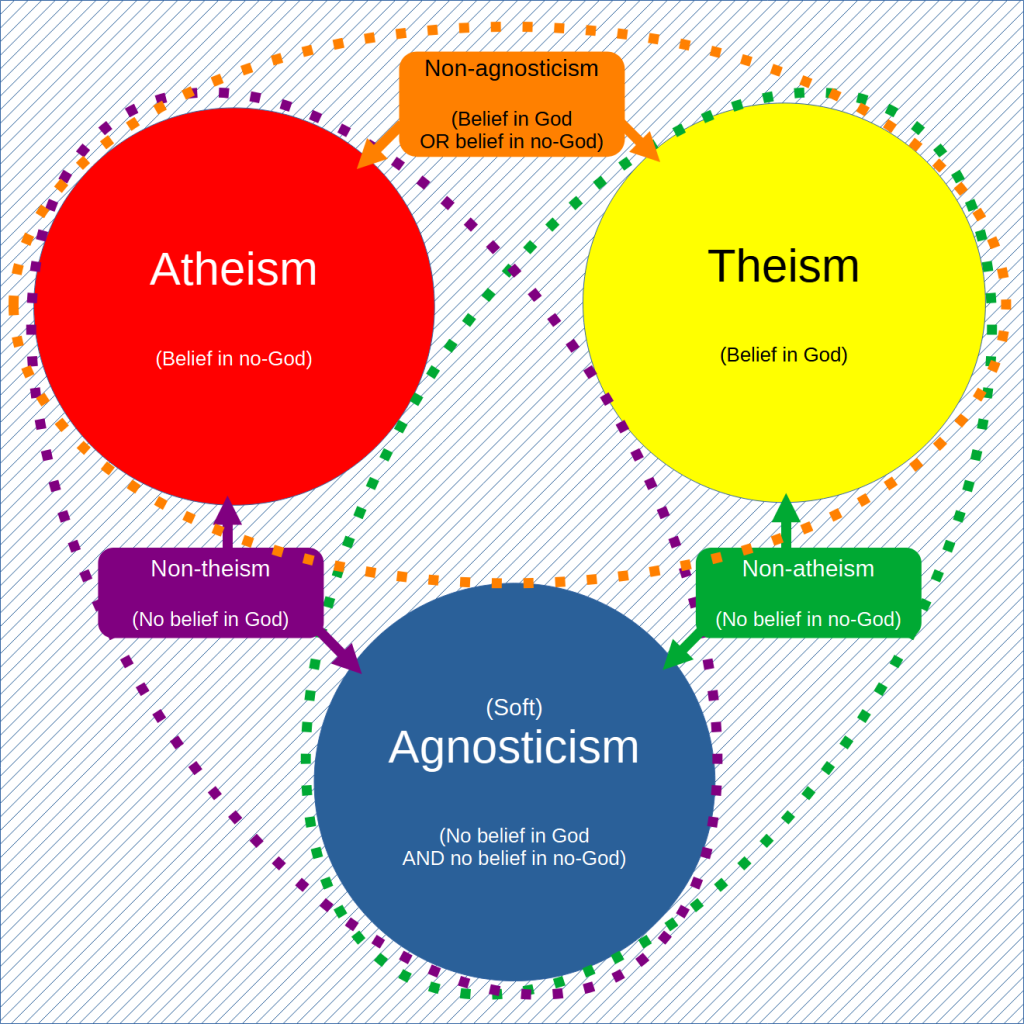

Agnosticism

What is agnosticism? There are two different things that are called agnosticism, known as strong and weak agnosticism, or positive and negative agnosticism, or hard and soft agnosticism. (All of these alternate terms, “weak”/”negative”/”soft”, are rather connotationally unfortunate. They don’t really seem like the kind of words people would want to be called. But I figure “soft” is probably the least bad of these options, so that’s the one I’m gonna choose to use.)

Hard agnosticism

Hard agnosticism is the belief that it’s impossible to know whether there is a God or not. So is hard agnosticism about knowledge, as opposed to mere belief? Sort of, but it is ultimately still defined in terms of a belief: Whether you’re a hard agnostic is not determined by whether you have a certain piece of knowledge, but by whether you have a certain belief about knowledge.

No position regarding the existence of God, not even hard agnosticism, can be defined as knowing (or not knowing) that some particular answer to the God question is true. That’s because one of the requirements for a belief to count as knowledge is that the belief is true.

So if, say, theism was defined as knowing that there is a God, you wouldn’t be able to talk about theism without implying that you agree with it. Nor would you be able to talk about atheism without implying that you agree with that. So these things need to be defined as believing (or not believing) something. Theism, atheism, and agnosticism are about what you believe or don’t believe, not about what you know or don’t know. Even hard agnosticism is just a belief about what we don’t know.

People might sometimes describe their beliefs as “knowing”, even if they don’t really mean to assert anything stronger than belief. That’s to be expected, because if you believe something is true, then you probably also believe that your belief has all the other requirements to count as knowledge. So that’s how you might talk about what you think, but that doesn’t mean that these things are actually about knowledge as opposed to belief. Not even agnosticism, and certainly not soft agnosticism.

Soft agnosticism

What is soft agnosticism? When I look at online resources that define agnosticism, they mostly seem to focus primarily on hard agnosticism. But they also (usually rather vaguely) define the soft kind as well. And their descriptions of soft agnosticism do seem compatible with it being about belief, and not actually being about a question of knowledge distinct from the question of belief.

A soft agnostic’s answer to the question of whether there is a God is “I don’t know”. But are people really talking about knowledge as opposed to mere belief when they say that? I don’t think they are.

Answering a question with “I don’t know” would normally most likely mean something like “I don’t know which answer I should give to that question”, or “I don’t know what to believe”. I would not expect someone who gave that answer to mean something like “Whatever I might believe about that, my belief is not properly justified and does not count as knowledge”.

Because as I said before, if you believe something, that generally comes with believing that your belief has all the requirements for it to be knowledge. So it would be pretty strange to believe something, but not to consider it to be something that you know.

Unless you’re saying you have faith, but if you had faith, you wouldn’t be an agnostic, would you? Or is everyone who has faith in God an agnostic, because they merely believe but don’t know that God exists (since their belief lacks the kind of justification that would be required for a belief to be knowledge)? No, they’re not. Or at least they’re not soft agnostics, because that’s not what the soft agnostic’s answer “I don’t know” means.

If you ask people whether there’s a God, you’re looking to find out what they believe. You’re not asking about anything to do with knowledge as opposed to mere belief. And people you ask may answer using an expression that happens to contain the word “know”, but that doesn’t mean they’re randomly deciding to answer that question with something irrelevant about knowledge, instead of actually addressing your intended question of what they believe.

I think people who answer that question with “I don’t know” are not really saying anything about knowledge. All they’re intending to say is simply that they don’t have a belief either way. So a soft agnostic is someone who lacks a belief that there’s a God, and also lacks a belief that there’s no God.

In other words, they have no opinion. They’re undecided. They’re suspending judgment. This is (and should be) the default state for the relation between any person and any claim, until the person comes to have a sufficiently good reason to either accept or reject the claim.

Soft agnosticism is a middle ground between believing that there’s a God and believing that there’s no God. Not to be confused with a middle ground between believing there’s a God and not believing there’s a God. There is no middle ground between those things; you have to do one or the other. But you don’t have to either believe there’s a God or believe there’s no God. It’s possible to have neither of those beliefs, which is what soft agnosticism is.

The principle of agnosticism

So those are the two main meanings that “agnosticism” has today, but the word actually had a different meaning originally. When Thomas Huxley coined the word “Agnosticism”, he didn’t intend it to mean either of the things that people use it to mean now.

What Huxley called agnosticism was the general principle that you should not act like you’re certain about something unless you have good evidence to support your opinion. (This was in response to the principle of faith, which claims that there are things you should believe with complete certainty regardless of the evidence or lack thereof.)

Neither the hard nor the soft modern senses of the word “agnostic” really seem to have much to do with its original meaning. But if I had to pick one, I’d say the soft meaning is closer to the original intent of the word. Because soft agnosticism and the principle of agnosticism are both fairly closely related to the principle of initially suspending judgment by default (which I mentioned a few paragraphs ago). I don’t know where people got the idea that agnosticism meant that knowledge about God’s existence is impossible.

Atheism

What is atheism? There are two different things that some people consider to both be forms of atheism, known as strong and weak atheism, or positive and negative atheism, or hard and soft atheism. (Again, I’m gonna go with hard and soft.) Hard atheism is the belief that there is no God, and soft atheism is a lack of belief that there is a God.

Hard atheism was originally the only thing that the term “atheism” meant. It’s what most people understand that word to mean. It’s how dictionaries say the word is used. And it’s what most philosophers use it to mean.3 But a lot of atheists now consider the broader category that they call “soft atheism” to be a form of atheism too. Some of them even say the soft version is the correct way to define atheism. Where did they get the idea that atheism is a lack of belief? Does it make sense to define atheism this way?

Some people have been trying to redefine atheism as soft atheism since Antony Flew in the 1970s: “Whereas nowadays the usual meaning of ‘atheist’ in English is ‘someone who asserts that there is no such being as God’, I want the word to be understood not positively but negatively.” (At least he acknowledged that his definition was not the standard definition of atheism.)

Some atheist activist groups are pushing this redefinition of atheism, not because it makes more sense, but mainly for practical agenda-driven purposes like inflating their demographic numbers by including soft agnostics as atheists. Are there any good reasons to define atheism as soft atheism? Are there any good reasons not to?

The atheist website EvilBible.com argues against the idea that “soft atheists” should be called atheists at all. That website lists several mostly good reasons to reject the “lack of belief” definition of atheism, and it also gives one particularly bad reason. (Which is the one that it asserts the most vehemently.) The bad reason is that English speakers commonly use “I don’t believe X” to mean “I believe X is false”. That’s not a good reason because:

- The fact that people commonly use language in illogical ways is no reason to accept those illogical uses of language. Normally, when the majority of people think or do a certain thing, intelligent people don’t take that as indisputable proof that the thing must be right. But for some reason, some people seem to think that the popular consensus can never be wrong when it comes to language.

- The fact that some people fail to make a distinction between two different things doesn’t mean there isn’t a distinction there to be made. And it doesn’t mean the distinction should not be made.

- And what are they even trying to prove with this argument? If this common usage argument was valid, what would the conclusion be? That everyone who says they “don’t believe” in God is an atheist? That’s basically the opposite of the point that EvilBible is trying to make! Their argument #6 seems to directly contradict their argument #8, or rather to make the same stupid error that their argument #8 calls out. Why are they arguing against their own position??

“Soft atheism” is not atheism

I think some of EvilBible’s other arguments for limiting the term “atheism” to hard atheism are pretty good, though:

- Some atheists say it doesn’t matter how most people use the word, because only atheists should get to define atheism.

- EvilBible points out that that is not how words get their meanings. The word “baby”, for instance, means what it means because that’s how we all use that word, not because babies decided that that was what it would mean.

- I’d like to also point out (though EvilBible doesn’t mention this) that this principle of exclusive self-definition can’t work, because you would have to already know what an atheist is before you would know who gets to define it.

- When people argue that atheism shouldn’t be defined as only hard atheism because it should be defined by atheists, they are assuming that most atheists want it to be defined as soft atheism.

- EvilBible notes that no evidence is being provided for this idea. (EvilBible then tries to further counter it with some statistics about people who report having “no religion”. But that could mean unaffiliated theists, so those stats are irrelevant and don’t really tell us anything.)

- Anyway, like I said, you can’t solely use what atheists think as the basis for defining atheism, because you would have to already know what an atheist is before you could know who to ask and who to ignore.

- Some atheists think it gives them a debating advantage if they can say they don’t have a belief or are not making a claim, and therefore have no burden of proof.4

- EvilBible responds that the people making the extraordinary claim that there is a God already have a massive burden of proof, so shifting the burden of proof onto them really isn’t necessary.

- Another response I’ve seen (not from EvilBible) is that if atheists want to be rational and to be seen as rational, they shouldn’t be trying to avoid the burden of proof just to try to make things easier on themselves.

- Especially if we’re talking about people who do actually have a belief that there’s no God. Why pretend you don’t? Trying to avoid the burden of proof just gives the impression that you’re unable to justify your position. You do have good reasons to think there’s no God, don’t you? I do. I don’t see why atheists would have a problem with having a burden of proof.

- If you really don’t have a belief that there’s no God, then you may legitimately have the debating advantage of having no burden of proof, because then your position really is the default position, which is soft agnosticism. But then why insist on calling it atheism? And why would you be debating the existence of God, and care about whether you have an “advantage”, if you don’t have an opinion on the matter?

- Etymology doesn’t necessarily tell you how a word should be used today, but for what it’s worth, the origin of the word “atheism” involved combining “atheos” with “-ism” (godless + belief), not combining “a-” with “theism” (without + belief in God).

- The EvilBible article on defining atheism concludes by extensively quoting several reputable dictionaries and encyclopedias. None of them define atheism as a lack of belief. All of them basically define atheism as either the belief that there is no God, or the “disbelief” in or “denial” of the existence of God.

- And they define denial as declaring something not to be true. And they note that denying the existence of God is something agnostics don’t do,5 unlike atheists.

- The dictionaries similarly define disbelief as rejecting something as untrue, or being persuaded that an assertion is not true. One of the dictionaries contrasts unbelief (merely tentatively not accepting that something is true) with disbelief (being convinced that something is false).

- The quoted dictionaries only define disbelief this way half the time, though. And a few of them do include a definition of disbelief as “not believing”. But I’ll note that since people do often (illogically) use that to mean believing that something is false, it’s possible that those dictionary writers didn’t really mean to say that disbelief means “not believing”. Especially since one of the dictionaries that says that is the same one that repeatedly makes the point that to disbelieve something is to believe it’s false.

Here’s another problem (in addition to the ones listed on EvilBible.com) with labeling people who merely lack belief as atheists. I believe this argument was first made by atheist philosopher Graham Oppy:

If not believing that there’s a God is a form of atheism, then by the same logic, not believing that there’s no God must be a form of theism. And if you lack both beliefs (the belief in a God and the belief in no God), then it makes exactly as much sense to say you’re a soft theist as to say you’re an soft atheist.

If it’s wrong to call such a person a theist, then it’s equally wrong to call that person an atheist. Because calling yourself an atheist when you merely lack a belief that there’s a God makes as much sense as calling yourself a theist when you merely lack a belief that there’s no God. If you call “soft atheists” atheists, then you have to accept that a soft agnostic (someone who is neither a hard theist nor a hard atheist) would be both a theist and an atheist.

But you can’t be both of those things at the same time, can you? This absurd conclusion, that someone can simultaneously be both a theist and an atheist, shows that there must have been a wrong assumption somewhere, that should be rejected. And that wrong assumption is that mere lack of belief in God is atheism. It’s not. Lack of belief in God is called non-theism. And when combined with a lack of belief that there’s no God, it’s soft agnosticism.

It’s called non-theism

- Everyone is either a theist or a non-theist.

- Everyone is either an atheist or a non-atheist.

- Everyone is either an agnostic or a non-agnostic.

- All non-theists are either atheists or agnostics.

- All non-atheists are either theists or agnostics.

- All non-agnostics are either theists or atheists.

- No one is both a theist and an atheist.

- No one is both a theist and an agnostic.

- No one is both an atheist and an agnostic.

- Anyone who is both a non-theist and a non-atheist is an agnostic.

- Anyone who is both a non-theist and a non-agnostic is an atheist.

- Anyone who is both a non-atheist and a non-agnostic is a theist.

(By “agnostic” here, I mean a soft agnostic. Hard agnosticism is a separate variable, and it’s logically possible to combine that with soft agnosticism, theism, or atheism.)

Agnostic atheism?

Can someone be both an agnostic and an atheist? It depends on what you mean by “agnostic” and “atheist”…

Continue reading Defining agnosticism, atheism, and agnostic atheism

The Story of Ananias and Sapphira—

The Communist Cult

The disciples of Jesus were given the ability to perform miracles better than Jesus, and they convinced thousands of people to join their new religion. The members of this original Christian church didn’t keep any personal property; they shared everything they had. Everything they earned had to be brought to their leaders to be distributed among the community according to their needs.

The goal was for everyone to be equally well off, with no one having too little or too much. Everyone was to be paid the same regardless of how much or how little work they did, just as Jesus (and his ancestor David) had taught.

Continue reading The Story of Ananias and Sapphira—The Communist Cult

The Story of the Crucifixion of Jesus—

Jesus Goes Back Home for the Weekend

Mad, bad, or God?

Jesus spent a lot of time with disreputable people. He violated the sabbath law, and encouraged others to do the same. When he saw people trying to enforce God’s law, Jesus got in the way. He told his followers to further break God’s laws by refusing to take oaths, eating unclean food, drinking blood, and hating their parents.

Jesus would go on long rants against the Jewish religious leaders. He acted like he thought he was God. He cured some people’s disabilities, only to give them to others. Jesus rudely discriminated against foreigners when they begged him to heal their children. He performed exorcisms despite knowing that it would make people worse off in the end. He sent a legion of demons to massacre someone’s livestock, just because the demons asked him to. This made everyone in that town want Jesus to go away. So he did.

Jesus said he was there to save the world, but he really just wanted to watch the world burn. He went into the temple and wrecked everything and chased the people out with a whip. He promised that those who followed him would not be excessively burdened, but then he required people to do completely pointless and unreasonably unpleasant things.

Jesus insisted on talking in confusing parables, and then got mad when no one understood him. The more he talked to people, the more they hated him. But he couldn’t figure out why. He offered people a reward, but said they could only get it if they didn’t expect a reward. People thought he was demon-possessed. Even his own family thought he was crazy.

God betrays Jesus

But there were also a lot of people who were convinced that Jesus was the Messiah, which the Jewish leaders were worried would get the Jews in big trouble with their Roman overlords. God inspired the high priest to point out that it would be better for one man to die than for the whole Jewish nation to be destroyed over the treasonous claim that Jesus was their king. So the Jewish religious leaders that Jesus had so often disparaged plotted to get him killed. Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples, agreed to get paid to hand Jesus over to them.

Jesus knew what they were planning, and he didn’t want to die. He repeatedly asked God to prevent his death if that was possible. But even though it was possible, God chose not to save him, because he wanted to see him suffer. God wanted to strike Jesus with a sword. How else could God demonstrate his righteousness and justice, if not by getting his innocent son killed instead of punishing all the actual evil people? Unless Jesus let himself be killed, God wouldn’t love him anymore.

Judas “betrays” Jesus

The religious leaders sent soldiers to arrest Jesus. Judas had arranged to let them know who they were after by kissing Jesus. But Jesus told them who he was himself, so Judas didn’t actually have to do anything. But he kissed Jesus and got paid for betraying him anyway. Later, Judas decided he didn’t want that money, and gave it back to the religious leaders, and he also used it to buy a field.

The soldiers took Jesus to the high priest. After he was questioned by the high priest, Jesus was sent off to the high priest, who for some reason wanted to know if Jesus was the son of God. When Jesus replied that he was, the high priest was shocked that Jesus would say such a thing, and the Jewish religious leaders said Jesus should be put to death for blasphemy. But though the Jewish law said Jesus had to be killed, the Jews didn’t have the right to execute anyone under Roman law.

So they handed him over to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, who for some reason thought Jesus was the king of the Jews. Even though no one but those astrologers had ever called him the “king of the Jews” before. And even though the Jews didn’t recognize him as their king. And even though Jesus had refused to become king of the Jews. And even though Jesus, being a descendant of Jehoiachin (AKA Jeconiah), wasn’t even eligible to be king of the Jews.

Pilate didn’t think Jesus had done anything wrong, and he wanted to release him. But the crowd insisted that he should be executed, because the Jewish leaders had somehow gotten all their people to suddenly stop liking Jesus.

So Pilate handed Jesus over to his soldiers to be crucified, while blaming the Jewish people for his decision and proclaiming himself to be innocent, as if he couldn’t overrule the commoners. (It was really God’s fault, though.) The soldiers stripped Jesus, stole his underwear for themselves, beat him, mocked him, and nailed him to a cross. He died, and was put in a tomb.

The totally convincing account of the resurrection

Continue reading The Story of the Crucifixion of Jesus—Jesus Goes Back Home for the Weekend

How to keep God from killing you

God kills people a lot. If you want to make sure God won’t kill you, maybe the stories in the Bible can help you figure out what you should or shouldn’t be doing. Here are some Bible-based tips for staying on God’s good side:

Things to avoid

- Don’t get too good at complimenting people.

- Don’t neglect to impregnate your brother’s wife.

- Don’t approach God when you’re not wearing the right underwear.

- Convince God to stay away from you. Otherwise, he might kill you just because he can’t control himself. You’re only safe if God is not with you.

- Never make offerings to God. It’s too easy to do it wrong and offend him.

- Never be happy about or indifferent to anything that God gets upset about.

- Don’t mourn when God murders your loved ones.

- If you want something, don’t ask God for it, because sometimes he acts like a malicious genie.

- Don’t tell the truth about how bad a job God is doing when he tries to do good things for people.

- If God gives you a place to live, don’t stay there.

- Don’t let your brother do a miracle slightly differently from how God wants it done.

- Don’t obey God. Don’t attack who God sends you to attack.

- Always listen to prophets when they tell you what to do. You’d better not criticize the prophets, or let anyone in your family criticize them either. Don’t try to tell prophets what to do, and don’t question their claims. Just blindly obey all prophets, even when they want you to injure them.

- Don’t listen to prophets who claim to be telling you what God wants you to do. They might be lying. If you take advice from God’s prophets, he might destroy your whole nation.

- Don’t marry a prophet, or God might decide to kill you just to try to make a point. (Even when he knows that won’t be an effective way to make his point.)

- Don’t marry God, if you’re a prostitute.

- Never fail to get advice from God, even when he refuses to give you any.

- Don’t look inside the ark of the covenant at the things that God told Moses to put there so people could look at them.

- Don’t try to protect the ark of the covenant.

- Don’t have wicked parents or children.

- Don’t have parents who do things God doesn’t want done. Or any other family members, either.

- Don’t let your parents conceive you in a sinful way.

- Don’t let any of your ancestors sin. Even if God forces them to.

- Don’t live in a country ruled by people with delusions of grandeur.

- Don’t live in a country governed by people who obey God.

- Stay away from lions when it’s time for God to feed them.

- Don’t roar at God.

- Don’t be a good person. God thinks killing good people is a good way to make sure nothing bad happens to them.

- If you’re a destroyer, don’t stop destroying, or God might decide it’s time for you to be destroyed.

- Don’t be anywhere near other people God wants to kill.

- Don’t whitewash your walls.

- Don’t think you’re wise, even if you are.

- Never retire.

- Don’t get mistaken for a god.

- Don’t be God’s son.

- Don’t resist when your community turns communist.

- Don’t follow or even learn about God’s law.

- Don’t be ignorant of God’s law.

- Don’t be unaware of who Jesus is, even when Jesus is actively trying to hide who he is.

- Don’t eat or drink anything unless you’re sure you’re doing it in a way that God approves of. If you eat too much, God might decide to destroy your city.